One of the quirks at Merton College is that people with junior research fellowships, e.g., like me, are also members of the College’s Governing Body. As expected, this means that I get to go to long meetings where we talk about everything from who to elect as new fellows to who donated how much money to the college to which publishers get to use which images from our library in their books to how much damage some drunk alumni caused at a party last week. Less expected was the letter I received recently from some government agency or other informing me of just how seriously I should take my new role as a trustee of a charitable institution. Anyway, much of life as part of the Governing Body is tedium, but sometimes it is interesting to see what matters look like from the other side than the side visible to most people. For example, Merton College is being featured all over the place today (e.g., in this Guardian article) after a Labour MP gave Merton pride of place in his story of racism, classism, elitism, and so forth at Cambridge and Oxford. Merton’s sin? Not admitting any black students in the last five years. Now it’s worth noting that anyone who actually knows how to do decent statistical analysis could have told you that that fact (were it such) might well just be statistical noise given the numbers of applicants involved. But, as it happens, there isn’t even any such fact. Mertonians who have with their very own eyes seen black students walking around — as recently as this year, no less! — are rather unimpressed with the MP’s research abilities.

Mistakes of that sort could be multiplied, but that, too, would become tedious. There is, however, a much more interesting problem with the numbers presented for Oxford as a whole. The claim is that black applicants are admitted at lower rates than white applicants. That claim is, I believe, actually true. But here we face the spectre of Simpson’s Paradox. Since that is one of my very favourite paradoxes, I can’t resist talking about it.

Imagine we are considering the effectiveness of two medical treatments A and B and we have two test populations X and Y. We test treatment A on part of population X and part of population Y. Ditto for treatment B. Now consider the following argument:

- A higher percentage of patients in population X taking treatment A recovered than those taking treatment B.

- A higher percentage of patients in population Y taking treatment A recovered than those taking treatment B.

- Therefore, a higher percentage of patients in the total population taking treatment A recovered than those taking treatment B.

Alternatively, suppose we have the aggregate data but not the data from the individual tests:

- A higher percentage of patients in the total population taking treatment B recovered than those taking treatment A.

- Therefore, in either population X or Y, a higher percentage of patients taking treatment B recovered than those taking treatment A.

The arguments look good, don’t they? But they’re bad. Both of them. And understanding Simpson’s Paradox will show you why. In short, Simpson’s Paradox shows that two variables can be correlated in a population but, when the population is partitioned, the same two variables can be inversely correlated.

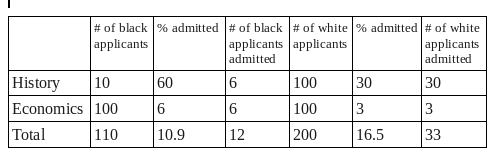

We’ll have to use some numbers to see how this works. But first imagine the following scenario: Old College has two departments (let’s not make this more difficult than it has to be): History and Engineering. History is an old, large department. Economics is newer and smaller. Economics, however, is more popular with incoming students than History is and so the acceptance rates are much lower than for History. The college is progressive and so, in an effort to redress wrongs, has instituted an affirmative action program on behalf of black applicants. The college has directed both departments to accept twice as high a percentage of black applicants as of white applicants. Imagine the college president’s horror, then, on the day he reads the following headline in the morning paper: “Racist Old College accepts 17% of white applicants but only 11% of black applicants”. Worse, the numbers are right. He can’t even respond by denying them.

This is where we’ll need numbers:

So how is it possible that each department favours black applicants and yet whites are admitted at a higher rate than blacks when we look at the college as a whole? Easy: black applicants are applying in larger numbers to the department that is harder to get into.

And that is at least part of the story at Oxford. An astonishingly high percentage of black applicants are directed to a handful of the subjects that are the most difficult to get into. Is that the complete explanation? I doubt it. Stories are seldom quite that straightforward. Is institutional racism a major factor? I doubt that, too, though I haven’t been around here long enough to have much insight into that question.

More general moral of the story: statistics are valuable, but, even when true, they need to be interpreted carefully.

And, isn’t Simpson’s Paradox fun? I wish I could discover something ingenious like that. For more on it, see here and here (the latter includes a bunch of real-life examples).

Sydney

Alan Schmierer

Alan Schmierer

OOohhh, that IS fun! Thanks for sharing!